The movie and entertainment industry at large has been embracing digital design for some time, and increasingly 3D Printing, with 3D printed props and assets used in movies ranging from Black Panther to First Man. Behind the scene, 3D artists and asset builders such as today’s #CyantistWeLove Christina Douk create 3D modeling, geometry and 3D printing magic to make characters and set designs appear! A past #3DTalk speaker, Christina has recently worked on films including Thor: Rognarok and Captain Marvel. In addition, she has created her own robot toy line and more! We are so excited to feature her, how she works each day, her advice to young Cyantists interested in this field, and of course, her favorite thing to draw! :)

Cyant: It is exciting to see how 3D modeling and 3D printing are being used in movies and are creating new visual effects and experiences. Can you describe how they have been part of your work in recent movies you have worked on?

Christina: Most of the work I do in feature film uses 3d modeling, where we build many assets for films as well as work with client files to optimize them for our production. I work on the 3d visualization side which incorporates: “pitchvis", a production that we do to give the clients an idea of what the film can look like before it is greenlit; “previs", the production where we develop the look and storytelling through set designing and shot creation; “techvis", the process of preparing camera and set information to assist with filming; and “postvis", the process of combining filmed plates with our CG work to give an idea of what the film looks like before sending it to finals visual effects companies.

Photo courtesy of Christina Douk: French Hallway Environment made for Eve Skylar from her concept - 2014

I've been a part of all of the processes building assets and more. Although my 3d printing side isn't visible on the screen, I use the knowledge that I've learned with printing in my modeling for production. There are times where I have to clean up and prep models from a client that are very high resolution, 3d scanned actors or environments, or models that contain geometry errors. I use Zbrush a majority of the time to clean up models and prepare them for “retopology” in Maya, so that we can use them in our workflow.

Photo courtesy of Christina Douk: An environment for the animated short Break Free by Nicole Ridgewell - 2012

Cyant: What is a typical day and what are the creative and technical processes you follow? How do you work with the other team members on the project?

Christina: A majority of the projects we work on are collaborative, so we are constantly working together. Usually we start off with asset builders like me who create the characters, environments or props needed per sequence. This process involves us modeling, texturing, lighting, and rigging every asset. And when we get to a good point, then we introduce shot creation which is where animation comes in to use the assets we make and compose shots to tell the story. When an new asset is requested or something breaks there's usually one asset person on hand to get it done. Depending on what process of production I'm in, my workflow uses Maya or Zbrush for modeling and UVing, then I texture using Substance Painter and bring it all back to Maya to finish up the model and rig and light them if I need to.

Photo courtesy of Christina Douk: First projects modeling and texturing for games - 2009 (Christina’s bedroom)

Photo courtesy of Christina Douk: A vehicle from Thailand made using games modeling technique - 2009.

Photo courtesy of Christina Douk: Robot fun using Modo - 2010

Cyant: What did you study and how do you think your studies prepared you? What did you have to learn?

Christina: I went to school for animation originally, but it never really clicked with me to be an animator. Within that process of studying though, I realized that I liked building sets and set dressing a lot more, so I geared my focus to that. I started taking classes that were more focused on game design and modeling and I felt a love for sculpting and building anything. Whenever I saw a beautiful concept I just wanted to build it in 3d because then I could see a design come to life. I kept on this path for many years, working in games first then commercials, toys, and now films all of which my knowledge has grown in each industry. I also take classes on 3d printing, clay sculpting, digital sculpting, drawing and pottery on the side to keep up with many skills and to expand creativity for myself. I never stop wanting to learn, and that continued growth has always fueled my want to keep making, designing and building.

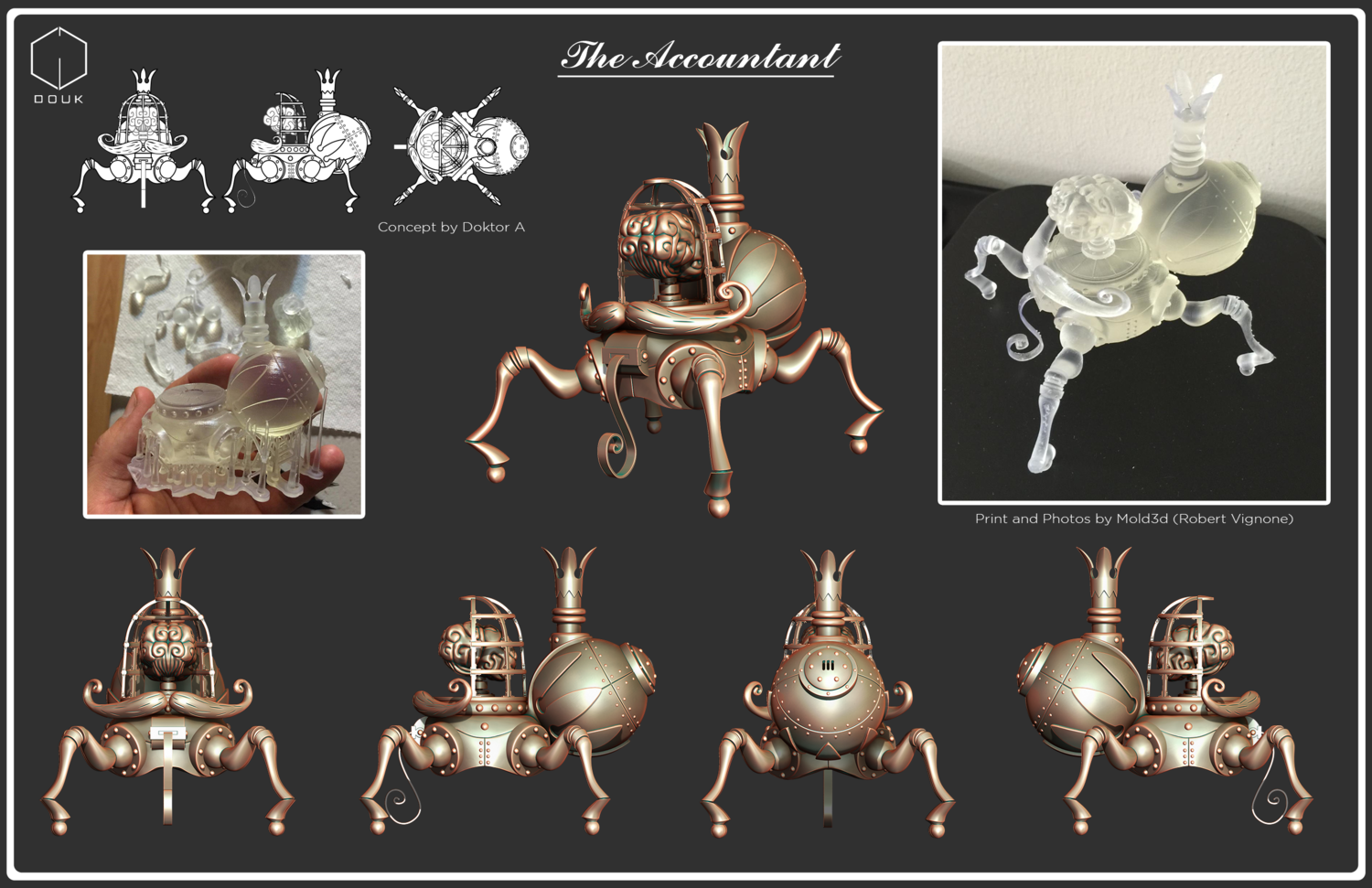

Photo courtesy of Christina Douk: The Accountant designed by Doktor A and produced by Mold 3d, modeled by Christina.

Photo courtesy of Christina Douk: Coal from A Dragon Named Coal by Rachel and Ash Blue

Cyant: You are also a creator of 3D printed toys! What inspired you to create these toys, and how is your work different, creatively and practically, from the work you do with movies? What has 3D printing enabled you to do? And what are some important lessons you've learned along the way?

Christina: This was a fun little side thing I love to do. I slowly came to this point where I wanted to do more than what my day job was. Once I found 3d printing and printed my first model and I realized this was a whole new market of creativity for me. I could make anything I wanted and produce it in a physical form. These little robots came out of some simple sketches I was working on for fun and I just kept drawing and modeling them. I’ve always been a fan of robots and these little guys always make me smile when I see them.

Photo courtesy of Christina Douk: First model made of the robots by Christina and a sketch over done by friend Tu Anh Nguyen to help figure out shapes and forms.

Making designer toys is a little different because the process involves closing the model up and making it watertight in one solid piece or multiple solid pieces with keys. There is some more planning on how I pose pieces too because I want to try and duplicate them by molding and casting as well. I start off using Maya to get basic shapes in and put together the look, since I am faster in that program, then I use Zbrush to combine all meshes and seal the model and prep it for print. Once the print is done, I let the model cure then break supports, sand it to the right smoothness and either prime it with spray paint or move on to making duplicates.

There were many routes that I wanted to take the toys, like mass production, but instead I wanted to control my own product and so I learned how to mold and cast pieces on my own, allowing me to make however many copies and I get to tint them to whatever color I want. It's a lot of fun producing my own work and I love how they all come out.

Photo courtesy of Christina Douk: First 3 robots created.

Cyant: On your Instagram feed, your tag line is: "Manipulating geometry one vertex at a time". As an artist, has working with 3D modeling and 3D printing changed how you use and view geometry and mathematics? How?

Christina: 3d modeling has changed the way I look at the world. I love geometric shapes maybe because of what I do, and I also have worked in this field for several years and noticed that sometimes how I look at the world is a little different. I break down items in our lives into simple geometric shapes and figure out how I can model them. My brain looks and sees repetition in buildings, cars, and products to see how can I optimize the amount of geometry to make that model. Sometimes if I work too much, I see the geometry and edge flow on the real life object, which can be weird, but is how my mind works these days and I find it interesting.

Photo courtesy of Christina Douk: Casted models of the robot design.

Cyant: What advice would you have for young (and not so young) cyantists who want to work with 3D modeling and 3D printing in the entertainment or game industry?

Christina: Just hit play. I really believe that once I started printing my own work I became more and more motivated to keep creating. And I think it's because having the physical product in front of you can show you and influence you that you can make anything. When I first started 3d printing I would model and sculpt many different things in preparation to getting my first printer, but even when I got that, there were so many complications with the ones I had, and there was one printer which didn’t work for me at all, so I ended up waiting another year to get my own. Instead, I ended up sending my stuff to print through a bureau and through friends in the meantime and that's when I realized that I wanted to design and create more. I'm a plug and play type of person. I want to focus more on the art and design vs the process of printing, so once I began making more and more content, I bought a printer to fit that mentality. I own a Form 2 at the moment and literally whenever I have an idea now, I'll model it, send it to print, and share it.

Cyant: And last but not least! What is your favorite drawing or thing to draw? :)

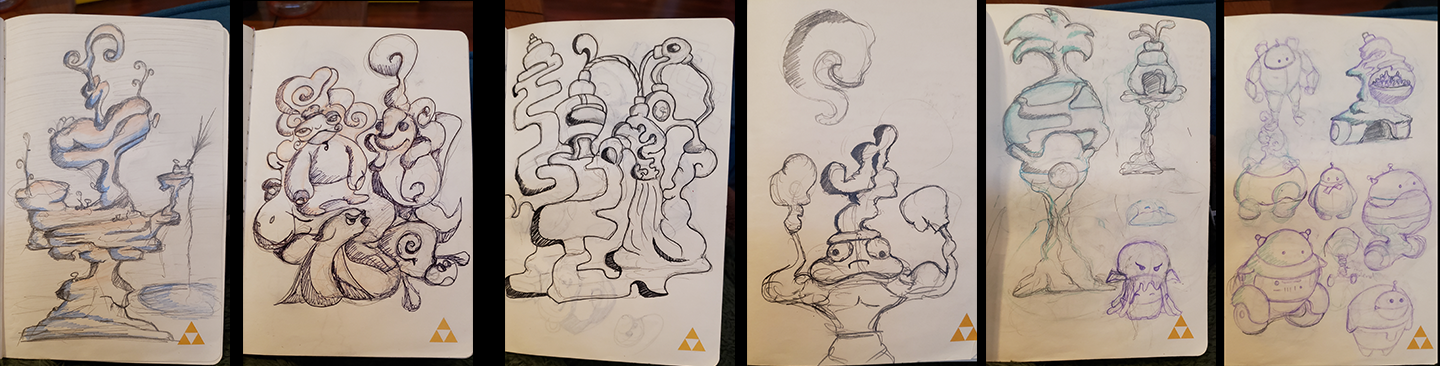

Christina: My favorite thing is drawing without a purpose. I don’t know what I will draw, but I doodle lines and see what comes out. It is like an icebreaker for myself, to break the need to draw something exact, I instead do whatever. My robots actually emerged from this method. Its freeing to kinda see where the lines go every time I do this.

Thanks so much for sharing your work and inspirations Christina! If you want to learn more about Christina, make sure to visit her website HERE and follow her Instagram account HERE!